It will take a global pandemic to force us to finally embrace home working

Around twenty years ago, almost to the month, I moved on from my first job after graduation and onto the next thing. It’s not uncommon for graduates to job-hop quite regularly in the years following graduation and I was no different, indeed, it’s very common in the IT industry. The job was no doubt a step up, there was no question of that. More responsibility, more money, cooler company, all that. But it came to me at a price.

My first job after graduation was around the corner from where I lived. This wasn’t an accident; the location of the job determined where I threw my hat when buying my first flat. So I bought it around the corner from the office. Why not? It was great, ten minute walk to and from the office each day, supermarket on the way home, no cost, no timetable, what’s not to like?

The next job, however, was much further away. Forty-five minutes in the car each way on a good day. An hour and a half on a bad one. No public transport options because, as cool as the converted sawmill in which the firm had established itself was, it was in the middle of nowhere.

Initially I didn’t mind. It was an exciting new job and and an exciting new chapter. But the long and frustrating commutes very soon started to wear thin, and I hankered for my old days of figuratively falling out of bed into my office. Most people have commutes in the order of 45 minutes to an hour, I realised that, but I had no idea how much of a drain on your quality of life they were until I actually had a proper one.

This is the thing with commutes: Nobody benefits from them.

- You don’t benefit from them: You lose more or less a working day per week of your own time to miserable soul-destroying journeys for which you’re forking-out over the odds anyway, whether that’s a train ticket or the costs of running a car. Even these days with fast mobile data connections you can’t really do anything in that time other than flick through your e-mails on your phone, and you certainly can’t do anything productive at all if you’re driving (I would hope not, anyway).

- Your employer doesn’t benefit from them: See the argument above about the severe limits to productivity even if you’re not fully engaged with controlling an automobile. Since commutes are often stressful this too can affect performance when actually at work. Train timetables also limit flexibility as to when you can leave and can often force tasks to remain unfinished at the end of the day.

- The transport systems don’t benefit from them: Both road and public transport systems are woefully inadequate for the population of the United Kingdom. They are extremely and often dangerously overcrowded and it doesn’t take much to make them grind to a complete halt. Quite often all it takes is rush hour, rather than something extraordinary like an accident or equipment failure. You have no control over this when it happens, and it means either you have to sacrifice even more of your time, or your employer has to sacrifice some time, or perhaps both, all depending on how understanding your employer is.

- The environment doesn’t benefit from them: All forms of transport use large amounts of energy, most of which is still non-renewable and produces harmful carbon emissions which are having a measurable effect on the global climate, as we are all too aware these days.

Around the same time I took my new job a revolution in home Internet connections was just starting. 2000 saw the introduction of the first consumer ADSL connections in homes, providing (normally) 512Kbps download speeds, around 10 times the speed of the previous dial-up technology, and it was always-on, meaning no metered call charges or connection time limits which were a common limitation of dial-up. It was, in effect, like having a cheap leased line in your house, since up until that point leased lines were the only means of obtaining and permanent and performant Internet connection.

With the roll-out of ADSL came another round of speculative news articles claiming that a home-working revolution was just around the corner because of it. I say another round, because it certainly wasn’t the first. The home-working revolution has been predicted as far back as the 1960s when Tomorrow’s World showed a man with a massive automatic typewriter next to his bed:

You can probably safely write-off the Tomorrow’s World segment as a pretty fanciful “what if?” possibility when broadcast at the time (the clue is in the name of the programme after all) and it did suggest that such technology would be preserve of the well-off rather than in widespread use – their example of someone requiring up to the minute stock prices using it would support this theory.

But regardless of how near and widespread the producers of the programme believed this new way of working was, it was at the very least the start of the idea. A utopia where many workers could do away with the grind of a commute and working in a fixed office, and enjoy the benefits of their home all the time whilst still being able to work and earn a living.

Over the following decades the predictions that home-working was coming resurged every now and then, with the introduction of things like fax machines, modem-based services such as Prestel, the eventual proliferation of the Internet outside of the military and academic worlds, dial-up Internet connections, faster dial-up Internet connections and ISDN if you were loaded. None delivered the home-working utopia. ADSL was no different, and right up until this year its successors (faster ADSL, fibre the cabinet, cable broadband, 4G, whatever) didn’t deliver it either.

But why?

Certainly, the proliferation of the Internet into the commercial world was enough to make a good start, even on dial-up connections. We still didn’t have video conferencing or voice over IP, but we could send and receive e-mails and documents attached to them. We also had access to company information and financial data, including those ever-important stock prices. It wasn’t perfect, and it was damned slow sometimes, but it was a far cry from Prestel or the man with the massive typewriter at the side of his bed.

The technology then only improved. Internet connections became faster, cheaper and more reliable. Wholly Internet-based companies started to appear, giving rise to the dotcom boom. Corporate, industry and financial data became instant. News became instantly accessible at any time. Can you really imagine a world now without online banking? Eventually all manner of video call and conferencing systems appeared – ropey at first, no doubt, but they too became dramatically better and did so very rapidly. Voice over IP now allows a corporate telephone system to be used pretty much anywhere, and even that’s a bit old-hat now with things like Microsoft Teams providing remarkable convergence and unification of e-mail, messaging, voice and video communication.

So where was our home-working utopia, despite all this? All we could see were the roads and the trains becoming ever-more crowded and ever-more expensive. Unless you were self-employed, everything pretty much remained the same.

The problem wasn’t technology. It was culture. And like with any cultural elements there were positives and negatives.

Let’s start with the positives. To do this I need to resume my original story of the earlier years of my career. I quit the job with the long commute sixteen months after starting it to set up on my own. As with most one-man bands, and fully-enabled with the blessing of ADSL, I began working from home. I evicted my flatmate and converted the second bedroom into a comfortable office. This arrangement persisted for three years, and partly enabled my move to Manchester, since the nature of my work and not being tied to an office meant that I could work from anywhere.

It was convenient, it was cheap, there was no commute, and it set me free in terms of where I could live – all clear and obvious benefits of working from home. But it wasn’t without its drawbacks. Although I admittedly was perhaps less disciplined in general in my younger years, I had no structure to my day. I would get up at 08:30 and make a cup of tea and then by 08:45 I was at my desk, very often still in my dressing gown. This of course meant I had to stop at some point during the morning and get washed and dressed properly, interrupting the working day. Then during the day there always seemed to be a long list of non-work todo items – shopping, things to do around the flat, household administration, whatever. All these things need to be done anyway, of course, but when you’re working from home they serve as a ready and inexhaustible source of procrastination. When you work in an office you can’t do those things until you leave. The afternoons and evenings often just blurred into one and I often found myself working at 22:00 and then having trouble sleeping because my brain was still going ten to the dozen – I have in more recent years discovered and enjoyed the benefits of “switching off” for a few hours before trying to sleep.

But these weren’t even the worst aspects. All of those were arguably easily solvable using a bit of maturity, structure and self-discipline, something which I did lack during the noughties. What was really missing from my working life was other people, that is, colleagues rather than customers or suppliers. So, we begin on the cultural negatives:

I had nobody to generally interact with. There was nobody to have a conversation with, bounce ideas off, or have check that whatever serious decisions you are making are even not batshit crazy, let alone correct and recommended. I didn’t learn from anyone, and nobody learned from me. I was a software engineer working on my own with no checks, balances or support, and, frankly, it really showed. I turned out some pretty terrible products during this time which I am not proud of. In my later career I have observed this in others, having taken on a project which was the result of someone having worked alone on it for many years. It’s every bit as a mess of the shit I turned out in the same circumstances, because they had no team or support structures in place to make sure that the decisions they were making were reasonable and that the output was appropriate.

I eventually resumed working in an office environment as part of a team, after a period of five years working alone. I can honestly say that doing so probably saved my professional career, and especially over the past decade I have absolutely thrived working as part of and then subsequently leading a team. We discuss, we challenge each other, we read each others’ code, we support each other when things go wrong, we learn from each others’ mistakes and the result of all this is not only greater skill, experience and wisdom, but also much better results. Right up until lockdown I could not imagine life any other way.

There are issues with corporate culture and home-working, however. Myself and my team are privileged – we enjoy what we do, having built careers out of hobbies. But we all know that not everybody has such passion in their jobs and a large proportion of people actively hate their jobs. The fear amongst corporate culture at large was that most people would be less productive and less disciplined if not working in an office environment. Management would be more difficult and, no, we simply can’t do this, no matter how good the technology has become, people simply cannot be trusted. We must stick with our ways, we must rent expensive offices, everyone must have a desk at which they must all sit between certain times fives days each week and they must be supervised to ensure they are not stealing time from the company. Meetings can only be face-to-face, we can’t really do proper business otherwise. You can’t be a team player and “feel the pain” when we’re busy if you’re not present in the bear-pit.

Without large-scale evidence to the contrary, these deep-rooted corporate beliefs, this corporate culture, endured. It probably would have endured forever. But then, that thing that happened this year, happened.

Within the space of less than a working week the majority of the UK’s white-collar office-based workforce had to change from attending the same office they had attended for years to working from home for the foreseeable future. It was seismic, and a huge undertaking, not least for the country’s IT departments (one of which is under my charge) who over the course of a matter of days had to produce vast numbers of extra laptops and scale-up resources such as remote desktop and VPN services. ISPs reported huge increases in traffic from their domestic customers and service providers such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams had to rapidly scale-up their infrastructure to meet an unprecedented increase in daily demand.

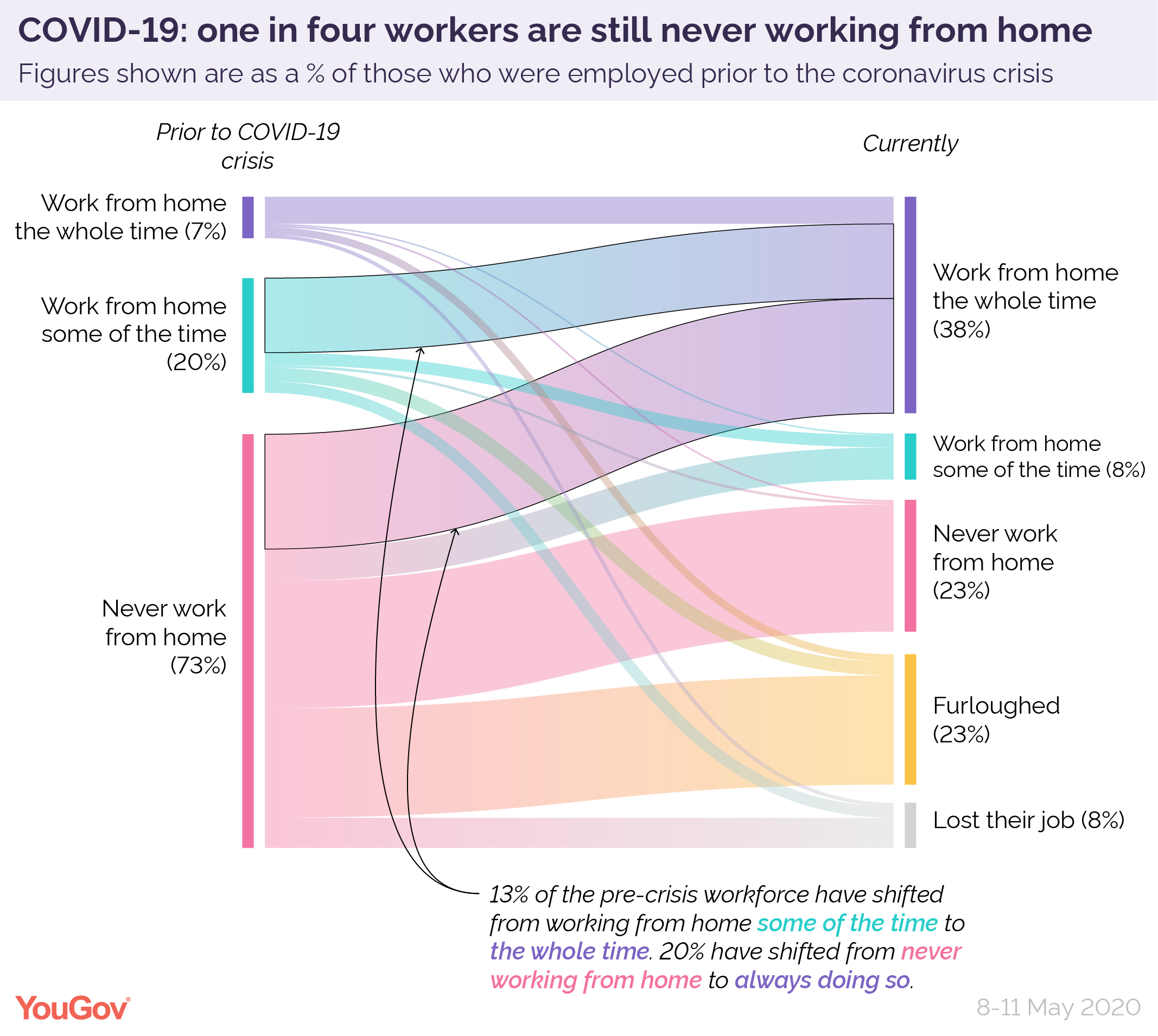

The graph below from YouGov shows the change in working arrangements for the UK workforce as a whole, whether they are offie workers, factory workers, care workers, whatever, so it underplays the more significant shift in arrangements specifically for office workers, which was far more seismic, but still illustrates nicely how the world was turned upside-down for many.

I absolutely hated it. I remained in the office for a long as I could, under the pretence that I still had more work to do to enable home-working for the company, but this ran dry only a few days after the company went home, and I too had to face the “new normal” (an insidious and sinister phrase which sends chills down my spine). The thought of not having that daily structure in my life and not being with my team every day, two things which I had utterly thrived upon during the last decade, filled me with dread. I remember the apathy, loneliness, procrastination, and indiscipline that working from home brought to my life previously and I most certainly did not want it back.

They say it takes a human being six to ten weeks to form a solid habit. This can be applied to pretty much anything – an exercise regime, an improvement in diet, a change in drinking or smoking habits; they all seem difficult, even insurmountable, at first, but if you can stick with it, or indeed if you are forced to stick with it, you become accustomed to it and it becomes a habit. Habits, once formed, are easy to stick to, although in fairness negative habits tend to be easier to stick to than positive habits.

Regardless, this is how it happened for me. I struggled in the first few weeks, made no better by the fact that I then caught Covid-19 at the tail end of April. But once I’d recovered from that and endured a few more weeks it all fell into place and I really found my rhythm and, sure enough, the habit was formed. In recent weeks I’ve been returning to the office in order to prepare it for socially-distanced re-opening, if that is what the company chooses to do (jury’s still out on that), and each trip, despite there not having been any significant traffic on the roads, has felt like a jolly great faff and inconvenience.

I’m not unique. I can’t speak for all firms, but the vast majority of our staff have adapted extremely well to the “new normal”. There have been a handful of exceptions, of course, nobody’s going to get a perfect record, but with those set aside the experience has been excellent and the company has not suffered. Indeed, at the end of May we completed on a deal which saw the whole group sold on to new investors, the preparations for which were almost all undertaken during lockdown. If we can sell our £200m company during lockdown then we can pretty much do anything. Not being in the office has made barely any difference to anyone’s productivity, even if it has destroyed all in-person social interaction.

With my team in particular I am fiercely proud of how they have adapted,. I feared that the lack of daily interaction would be detrimental to their mental wellbeing and their output, but none of that has happened. Ubiquitous technology has certainly helped in that regard. We’ve used software development collaboration tools to run the team for years, which proved to be even more important during lockdown, but the team also took to things like Microsoft Teams like ducks to water and use it extensively to stay in touch with each other all throughout the day, every day.

Would we have a challenge on-boarding a new member of staff during lockdown? Has the team only been able to succeed during lockdown because they were already a coherent and functional unit before it started? Absolutely, on both points. New team members always need a fair amount of training and hand-holding and we still believe that this would be extremely difficult for a new team member working on their own who’s never met their teammates and hasn’t built up those strong dynamics with them gained through working in the same physical space. But, as I will now move onto, I’m not saying that home-working is now appropriate for everyone, all of the time, moving forward.

So what does the future look like? Well, first, it’s important to acknowledge and accept that much of the “corporate culture” that held us back from widespread home-working in the past has been proven to be mostly bollocks. We’ve just had a massive global experiment to prove that it was bollocks. Fate has forced our hand and it has taken a global pandemic to make us face up to the fact that full-time office working for everyone is simply not necessary and is wasteful of corporate, personal and climatic resources. Hallelujah, an epiphany at last. We can no longer cling to our outdated corporate culture excuses, the genie is well and truly out of the bottle, the cat is well and truly out of the bag, and neither have any intention of re-entering either vessel.

I don’t see a future where we return to the world as it was before. Not now, not in three months, not after Christmas, never. It will never be the again because it does not need to be. Nor do I see I future where all office workers continue to work from home full-time either. Neither arrangement is ideal. What I see is a jolly great mashup of the two, which suits employers and employees alike.

The option to work from home from between one and five days per week will become the norm, and may even be enshrined as employment rights one day. Employers will be able to reduce their office space requirements by abolishing many full-time desks and replacing others with more “hot desks” which employees can use according to whichever rota they choose to manage the days on which they work in the office. Offices will become more like corporate hubs than full-time places of work.

Companies will find they are able to tap into a much wider (and potentially cheaper, in the case of those based in London) workforce since geographic location will be far less important. I, for example, would happily accept a position in a London-based company and travel to the office one day per week. Before lockdown such opportunities would have been out of reach to me because I do not want to live in London or its commuter belt. Families will have greater freedom to live wherever they want without fear of compromising employment opportunities. Towns and cities will enjoy less overcrowding as living close to places of work becomes less necessary. House prices in such areas will become more affordable as a result.

The provision of home working facilities, whether that’s computer equipment, broadband connections or furniture kits will become a standard offering. The latter is important since not everyone had a nice comfy home office during lockdown and many were stuck on dining room tables, far from ideal. The government could even allow employed home-workers to claim a portion of their rent and bills against tax if they have converted a room dedicated for home-working, much like self-employed people do already. Positions will be designed around a “remote working first” principle – they will have to be, because you can bet your bottom dollar this won’t be the last lockdown-inducing pandemic we’ll ever see, and to be unprepared for the next one after this experience would just be negligent.

Strain on the transport systems will be relieved. We’ve already seen the world as it could be on the roads and trains during lockdown. We can’t expect it to be that quiet forever, but we shouldn’t allow it to return to the ludicrous levels it was at previously. Less transport usage equals less energy usage equals fewer carbon emissions and indeed less pressure to build further transport infrastructure, although it is arguable that we are so far behind with that already we shouldn’t use this as an excuse to not improve it.

I genuinely think that all this will happen quite quickly. We’ve had the massive push we needed. It’s a pity that it took a global pandemic to get us there rather than any sort of rationale, but here we are. That third week in March 2020 was the last time you’ll ever see all your colleagues in the office at the same time. You didn’t know it at the time, but that was a watershed moment in corporate history.

I’m looking forward to this new world. From hating the mere idea of home working at the start of the year I have learned to take advantage of it, both for myself and my team, and I have to say that I am happier for it. Covid-19 will leave its mark on our world in many different ways, but this one will be positive.